In Veldhoven, a small municipality in the Netherlands, there is a company that holds the pulse of the technological future in its hands.

Its name does not appear in the advertisements of your devices or on the cases of your phones, but without it there would be no artificial intelligence, no state-of-the-art chips, and no cutting-edge scientific advances.

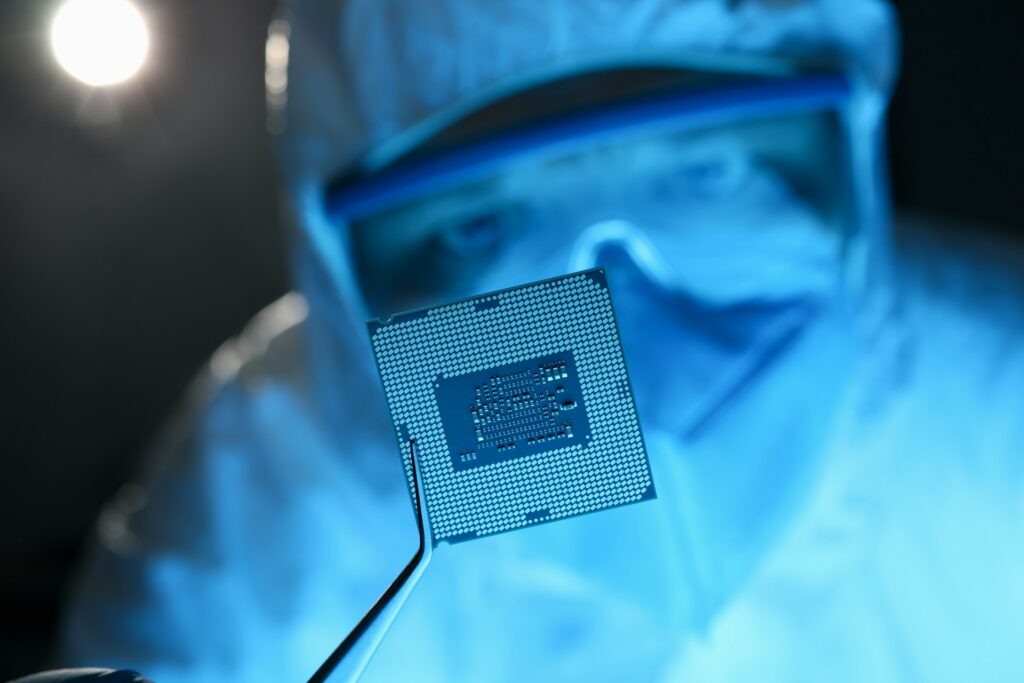

ASML, a firm that seems to come out of European anonymity, is the only manufacturer in the world of extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) machines, essential tools for “drawing” on silicon the most complex circuits used by humanity.

Without their equipment, the dreams of tomorrow’s computing would be frozen.

“A single company can change the course of technological history”

By: Gabriel E. Levy B.

The history of ASML began in 1984 as a joint venture between the Dutch firm Philips and the company Advanced Semiconductor Materials.

Its purpose was to manufacture lithography machines, a technique that was already essential for producing semiconductors.

But the real leap came decades later, when he decided to focus on the development of EUV (extreme ultraviolet) lithography, a system that uses wavelengths of 13.5 nanometers, a hundred times smaller than those of visible light, to create circuit patterns in silicon wafers.

That decision marked a turning point. While competitors such as Nikon and Canon were lagging behind, ASML poured billions of dollars and decades of research into a process that bordered on the impossible.

EUV lithography required optics so precise that only one company in the world, Carl Zeiss, could manufacture them; high-power lasers capable of vaporizing tin at 40,000 degrees Celsius, vacuum systems more complex than those in the aerospace industry and a supply chain that today integrates between 700 and 800 specialized suppliers.

That network not only achieved what seemed unattainable: it also created such a high barrier to entry that, to this day, no one else has managed to develop a comparable system.

ASML has no real competitors. Its monopoly on EUV lithography is absolute and its position is vital to any long-term technological plan.

“Without ASML, there is no artificial intelligence”

ASML’s relevance is not explained by its turnover, although it is multimillion-dollar, but by the place it occupies in the very structure of global digital power.

Every advanced chip used by artificial intelligence platforms, the latest generation of mobile phones, the servers that power the cloud, autonomous cars and even defense systems, requires an EUV machine manufactured by this Dutch company.

The logic is simple: the smaller the manufacturing node (7 nm, 5 nm, 3 nm), the more efficient, powerful, and faster the chips are.

But to achieve this level of miniaturization, it is essential to have ASML machines, which allow transistors to be recorded the size of molecules. And not only are these machines expensive, each one can cost between $150 million and $350 million, but they’re so complex that they can require more than 40 containers and weeks of on-site assembly to assemble.

ASML is a deliberate bottleneck. Its absolute dominance in EUV gives Europe a unique strategic lever over the global digital value chain.

But the power doesn’t just lie in technology. ASML, publicly traded and without a sole proprietorship, is mostly held by funds such as BlackRock, Vanguard and other institutional investors.

Its control is not centralized, but its influence is unquestionable.

Your decisions—which customers to sell to, when to deliver, how to scale your production—can affect the pace of global innovation. And that influence is largely invisible to the general public.

“The Limits of Power: Between the United States, China, and Silicon Diplomacy”

The world is no stranger to ASML’s geostrategic relevance.

In fact, one of the most palpable tensions on the global chessboard has access to its EUV machines as its axis.

The United States has in recent years pressured the Dutch government to restrict the export of these tools to China, arguing that they could be used for military purposes or to bolster the technological capabilities of its main geopolitical rival.

The Netherlands, historically defenders of free trade, had to bow to pressure.

In 2019, they vetoed the sale of an EUV equipment to the Chinese company SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation), after strong pressure from Washington.

Since then, every sale ASML makes must be authorized by the Dutch government, in line with export control policies imposed by the United States.

The situation reflects a dilemma:

Can a private company, which designs tools for scientific innovation, become a key player in international diplomacy?

According to George Yeo, Singapore’s former foreign minister and expert in technological geopolitics,

“ASML is not just a company; it is a piece of European sovereignty in a digital cold war.”

That’s why today’s technology map increasingly resembles a chessboard where every move by ASML can accelerate or slow down the advancement of artificial intelligence, quantum computing, or cyber defense.

The company says it does not make political decisions. But its tools are at the heart of all relevant policy decisions.

“The cases that reveal the control of innovation”

The most paradigmatic case is that of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the Taiwanese company that manufactures 90% of the world’s advanced chips.

TSMC is ASML’s main customer and also its best example of how EUV machines allow you to climb the frontier of the possible.

Without ASML, TSMC would not be able to manufacture the 3nm chips that Apple uses today in its iPhones and that Nvidia needs to train artificial intelligence models such as GPT-4 or Gemini.

In other words: without Veldhoven, there is no Silicon Valley. The interdependence is total, but also asymmetrical.

At the other extreme, China struggles to achieve technological self-sufficiency.

Companies like SMIC tried to replicate advanced lithography capabilities,

but without access to EUV machines they could not go beyond 14 nm nodes. Although they have developed some alternatives, such as the intensive use of DUV (deep ultraviolet) lithography to manufacture 7 nm chips in an artisanal way, the qualitative leap is still out of reach without ASML.

The United States, for its part, invested tens of billions in its CHIPS Act to attract semiconductor factories to its territory, but none of them can operate with EUV lithography without resorting to ASML.

Intel, for example, recently closed a contract worth more than $4 billion to acquire new EUV units in an attempt to regain competitiveness.

In Europe, governments celebrate ASML as an industrial bastion, but they also worry about the structural dependency it represents.

If a single point in the production chain fails, if Carl Zeiss stops manufacturing its optics, if a key supplier goes into crisis, the entire ecosystem can collapse.

In conclusion, ASML is not just any company. It is the invisible node that sustains the future of artificial intelligence, high-performance computing, electronic miniaturization and even the national security of the great powers. Its role as the sole supplier of EUV lithography makes it an unprecedented strategic piece in modern industrial history. As the world moves into a hyper-connected and technologically dependent era, ASML’s power grows quietly, proving that sometimes, control of the future fits into a single factory surrounded by tulips.

References

- Miller, Chris (2022). Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology. Scribner.

- Jensen, C. S. (2023). Geopolitics of Technological Dependencies. European Council on Foreign Relations.

- Yeo, George (2021). Lecture on technological geopolitics at Tsinghua University.

- Financial and technical reports of ASML Holding NV.

- Documentation of the CHIPS and Science Act (USA, 2022).