It was recently reported that Delta Air Lines was exploring an artificial intelligence model capable of adjusting air ticket prices according to the reason for each passenger’s trip.

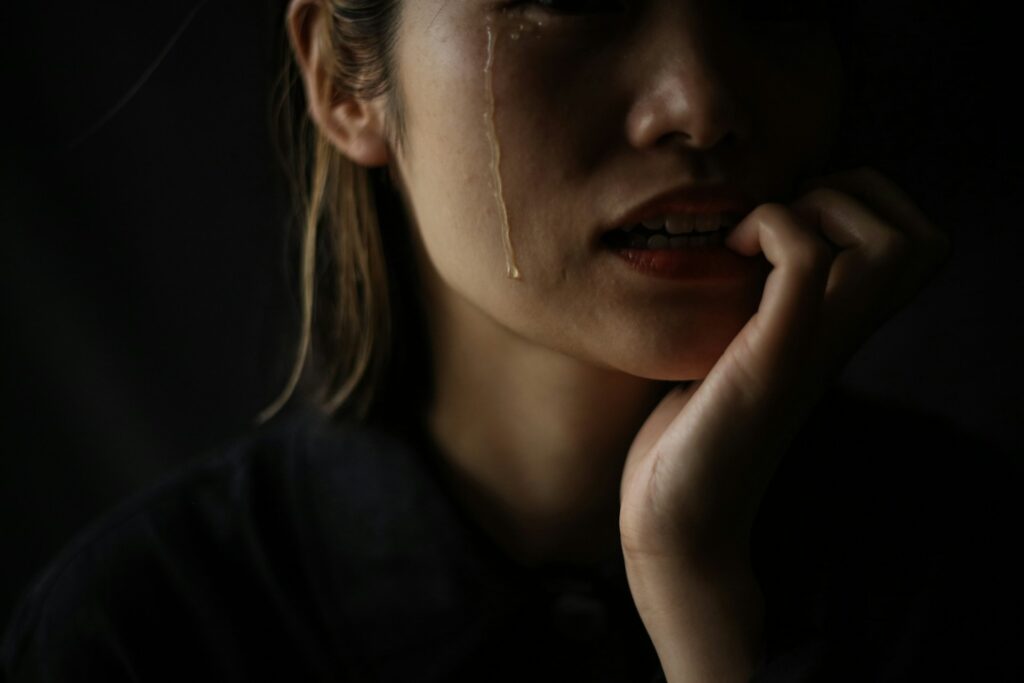

The idea was unsettling: an algorithm could charge more to those who flew in an emergency for the death of a family member than to those who traveled on vacation. What seemed like an efficient business strategy sparked a debate about privacy, dignity and the ethical limits of digital trade.

The danger concept of the Economy of Emotions

By: Gabriel E. Levy B

For decades, artificial intelligence was imagined as a mechanism to free human beings from repetitive tasks and open up new creative possibilities.

Marvin Minsky, a pioneer at MIT, wrote in the 1970s that intelligent machines would make it possible to “expand the human mind into as yet unknown territories.”

The optimism of that time marked the beginning of a story full of promises of efficiency and progress.

However, in parallel to this technological narrative, a fundamental concept emerged to understand the present: “the economy of emotions”.

This term, worked on by authors such as Eva Illouz, describes the way in which feelings, passions and affective experiences cease to be intimate spheres to become economic resources: love, sadness, anxiety or grief are managed, regulated and transformed into merchandise by a market that has learned to capitalize on people’s moods.

The combination of this economy of emotions with artificial intelligence is explosive.

What started with search algorithms and recommendation engines soon transformed into systems capable of tracking emotions, preferences, and states of vulnerability with an unprecedented level of accuracy.

In the business sphere, technology giants and airlines such as Delta Air Lines are already exploring the possibility of using artificial intelligence to set prices according to the emotional profile of passengers.

It is not only a matter of measuring the willingness to pay, but of delving into the most sensitive moments of life: a traveler who bought a ticket to attend a funeral could pay more than someone who bought the same route for a vacation.

Sadness or urgency translates into opportunities for profitability.

These types of applications are not simple futuristic hypotheses.

They represent the way AI systems learn to exploit our human weaknesses for the benefit of the market, integrating emotions as new economic variables.

What was once presented as algorithmic neutrality is now transformed into a scenario full of ethical dilemmas, where the boundary between efficiency and abuse is increasingly blurred.

The economy of emotions, powered by artificial intelligence, ceases to be a cultural or academic phenomenon to become the very core of contemporary business practices: a laboratory of manipulation where suffering, urgency and joy are inputs calculated by machines that decide how much our human experience is worth.

Artificial intelligence in the economy of emotions

Eva Illouz, in The Salvation of the Modern Soul (2010), explains that contemporary capitalism is not only based on material goods, but also on the commodification of emotional experience.

Pain, anxiety or joy become variables that determine how, when and how much we consume.

In this sense, the case of Delta Air Lines reveals how AI can be inserted into the economy of emotions to turn suffering into a resource for profitability.

The algorithm doesn’t simply look at cold supply and demand data; Interpret the emotional load of the moment to set a price that maximizes revenue. L

or that used to be an air ticket is now transformed into a product adjusted to the emotional vulnerability of the passenger.

Another key author, Antonio Damasio, in Descartes’ Error (1994), argues that emotions are at the core of all human decision-making.

If companies know this and AI is able to detect these emotional states through digital behavior patterns, the commodification of emotion ceases to be abstract and becomes a concrete operation: taking advantage of fear, urgency or sadness as economic inputs.

The initial appeal of AI as a personalization tool becomes, little by little, an invisible control mechanism.

In the economy of emotions, the consumer not only acquires a service; he unknowingly offers his affective intimacy as raw material for the profitability of the market.

Algorithms as devices of emotional power

The central question is whether the abuse of artificial intelligence constitutes a simple distortion of the market or a renewed form of emotional domination.

Byung-Chul Han, in Psychopolitics (2014), warns that digital technologies do not directly repress, but rather shape desires and decisions from within, under the guise of freedom.

The user believes he chooses, when in reality he responds to a carefully designed affective conditioning.

The problem is aggravated to the extent that emotions become a commodity. In the emotional economy, an algorithm that knows that someone has lost a family member does not see a human drama, but an opportunity for income.

This instrumental reduction of subjective experience constitutes a new form of symbolic violence.

This is not an isolated case. Political microtargeting during Brexit or the 2016 US elections showed how emotional manipulation became a central strategy: messages designed to generate fear, indignation or electoral euphoria according to the psychological profile of each voter.

AI not only predicted moods, but exacerbated them to shape collective decisions.

The real risk lies in the opacity of the system. Unlike human interaction, which can be questioned, the algorithm is presented as neutral, technical, incontestable.

Thus, emotions cease to be the patrimony of the individual to become a terrain exploited by corporations under a logic of algorithmic power.

The background of algorithmic emotional economy

The abuses derived from the emotional economy mediated by AI have already left visible traces in different sectors.

One of the most controversial cases occurred in 2019, when Apple Card was found to grant significantly lower credit limits to women than to men with similar financial profiles.

The algorithm did not discriminate only by economic data, but incorporated biases that replicated structural inequalities.

In Illouz’s terms, gender became an emotional and symbolic variable translated into financial inequality.

Another case occurred in the Netherlands with the SyRI system, which sought to detect fraud in social benefits.

There, entire neighborhoods were classified as “high risk” based on variables that mixed economic condition with cultural prejudices.

The impact was devastating: communities stigmatized under an algorithmic cloak that treated social vulnerability as a threat.

In the United States, predictive software such as PredPol reinforced the criminalization of African-American and Latino communities.

The algorithm, fed by historical arrest data, assigned greater police surveillance to these neighborhoods, generating a cycle of fear and mistrust.

Here the collective emotion, the fear of insecurity, was instrumentalized as a political and operational resource.

Even in the educational field, during the pandemic, remote surveillance systems accused students of fraud by simple head movements. The anguish and anxiety generated became byproducts of a control model based on algorithmic suspicion.

Each of these cases reveals how the emotional economy unfolds on multiple levels: gender, poverty, security, education. They all translate into the same pattern: the capture of emotions by systems that transform them into opportunities for control and economic benefit.

In conclusion, the abusive use of artificial intelligence not only alters traditional economic dynamics, but also deepens the logic of the economy of emotions.

As Illouz and Damasio pointed out, our decisions are never purely rational, they always go through an emotional framework.

The disturbing thing is that now these emotions are detected, classified and exploited by opaque algorithms that turn them into merchandise.

The contemporary challenge is not only to regulate prices or protect data, but to defend the right that our emotions do not become just another input in the digital market.

References Cited

- Minsky, Marvin

- The Society of Mind. Simon & Schuster, 1986.

(Reference to the MIT pioneer who imagined the expansion of the human mind thanks to intelligent machines.)

- The Society of Mind. Simon & Schuster, 1986.

- Zuboff, Shoshana

- The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. PublicAffairs, 2019.

(On how digital technologies turn human behavior into raw material for the data economy).

- The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. PublicAffairs, 2019.

- Han, Byung-Chul

- Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Power Techniques. Herder, 2014.

(On how digital technologies shape desires and emotions under the guise of freedom.)

- Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Power Techniques. Herder, 2014.

- Illouz, Eva

- The Salvation of the Modern Soul: Therapy, Emotions, and the Culture of Self-Help. Katz Editores, 2010.

(Theoretical basis of the concept of the economy of emotions and the commodification of feelings.)

- The Salvation of the Modern Soul: Therapy, Emotions, and the Culture of Self-Help. Katz Editores, 2010.

- Damasio, Antonio

- Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Putnam, 1994.

(On the centrality of emotions in human decision-making.)

- Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Putnam, 1994.

- Business Insider. “Delta’s AI pricing backlash shows the tightrope companies walk with AI adoption.” August 6, 2025.

- The Verge. “Delta is testing an AI-powered dynamic pricing model for flights.” August 7, 2025.