In recent years, there has been a considerable discussion of transmedia, a term that has become trendy for filmmakers, producers, scholars and people linked to the audiovisual sector. Although there are several different and acceptable definitions and approaches, it is a diverse and multifaceted field, its concept is used indiscriminately more as an ornament in media discourse, and in some cases its original meaning and context is distorted.

Producing transmedia is not easy, it requires design, planning, mysticism and above all, a lot of creativity and flexibility when creating, producing, managing and expanding content. This is a very powerful tool that has transformed the cultural industries in recent decades and needs to be implemented properly, otherwise it could go against the viability of the project itself.

This article aims to explain from multiple dimensions what transmedia is and why it is relevant to the cultural industries in the contemporary world.

What is transmedia storytelling and how can it be properly implemented?

Transmedia storytelling is a communicational strategy whereby content is designed and produced in a way that can be seamlessly expanded across multiple platforms, containers and screens, which can generate consumption alternatives and, consequently, impact multiple audiences. Some call it liquid content, others call it expansive content, but in any case, the idea is the same: To achieve enough flexibility so that the stories circulate in an articulated and subtle way through multiple scenarios and platforms.

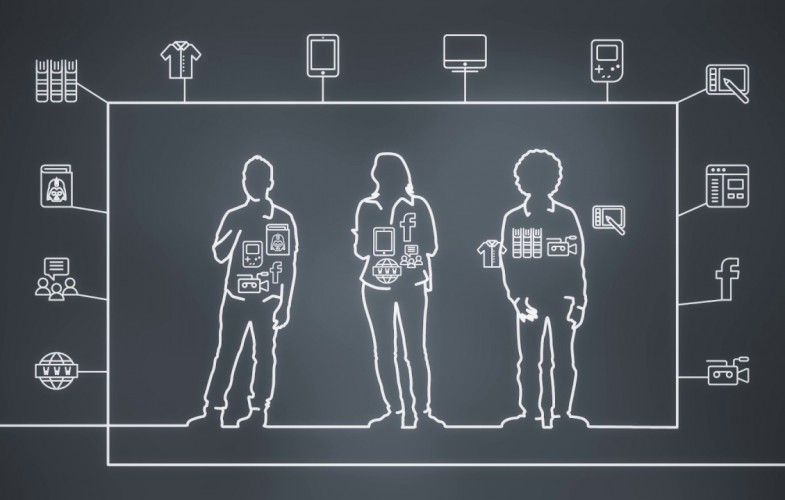

The condition for a project to be transmedia is that its narration must be hypermedia; that is, designed for multiple communicational supports. Regarding the type of content, we refer to audio, images, video, text, games, physical experiences and others; regarding media, we think of television channels, social media, VoD systems, websites, performances, among others, and when we talk about platforms, we refer to televisions, tablets, theater stages, etc.

These contents, platforms and containers can be connected to each other through hyperlinks that allow the experience to go beyond linearity, to move freely between scenarios, although the stories themselves and the stories that are told can still be narrated in a linear way.

The so-called Transmedia Universe is composed of four sub-levels. On the first level, encompassing the other three, is the franchise, a term borrowed from marketing and which calls and gathers together the entire project. On a second level is the central story or Universe, the main focus of the entire franchise. On the third level are the multiple stories, which feed the story and finally are those that become content that will expand each through different platforms, containers and scenarios. On the fourth level is the fandom or co-creative space whereby the story continues to grow organically thanks to the “fans” and collaborators.

An example to understand the concept of the Transmedia Universe is the expansion around the movie Matrix:

- The brand and original idea of Matrix constitute the franchise.

- On the next level, The Universe appears with its central story: “In the future, almost all human beings have been enslaved, after a harsh war, by the created machines and artificial intelligences. These have them in suspension, and with their minds connected to a virtual reality that represents the end of the 20th century“.

- On the next level, there are hundreds of stories:

- There are multiple stories in the film trilogy about humans living together as slaves of machines and their struggle to be free.

- There are stories in the other containers and platforms (web, animated series, video games, social media, publications, etc.) that are not told in the trilogy, such as: how machines colonized humans.

- On the fourth level is the immersion of the viewers, the fandom with its co-creation, and the way they continue to expand the story through stories produced by themselves, which is called worlds by the American scholar Henry Jenkins.

Therefore, in order for a project to be worthy of the name transmedia, it must necessarily belong to, or be a franchise, with a central story that unfolds in multiple stories and that seeks to unleash a fandom or co-creative field.

Once the project has been set up on its four levels with a well-defined franchise, there are other fundamental tactics that must be applied as golden rules to guarantee the success of the transmedia project:

Autonomy: Each story must be able to tell a story by itself, regardless of the type of content it was created with, the container where it is published or the platform where it is consumed. If the story requires other content, containers or platforms for the story to be understood, the project may fail, as it is impossible to guarantee that the user will be encouraged to consume other types of stories from the franchise. In other words, as American theorist Robert Pratten explains: “Each story should be enough to understand the story, however, when the user consumes all the stories, the experience is certainly much more satisfying“.

Expansion: Each story must expand the story autonomously and have unique elements that other stories in the franchise have not brought to the story.

High quality canon: The invoice or quality of the products produced by the filmmaker in all its forms, contents, platforms and scenarios, should meet the highest possible quality, both on a storytelling and aesthetic level. This will allow the franchise to differentiate itself from a spontaneous co-creative project and to continue being the center of the fandom that is generated.

Organic Fandom: The level of interest and participation by the users must be developed organically, that is, the franchise itself must have the power to seduce the audiences to participate, interact and co-create, always avoiding that this participation is very forced.

Likewise, there are other aspects that should emerge spontaneously to guarantee the existence and consolidation of this organic fandom. Jenkins summarizes it in seven key aspects:

- Expansion vs. Depth: Expansion is the ability for stories to be derived into new stories, and the ability and commitment of fans to spread the content through different channels. Depth is the creation of content where the franchise universe can be deepened, as well as the search for more information about this universe. Expansion and depth go hand in hand.

- Continuity vs. Multiplicity: Continuity is the coherence in which audiences can follow the central story of the franchise through autonomous stories, but still maintain their connection to the official stories. Multiplicity is the creation of diverse stories, as well as the production of alternative versions of the characters or universes of the stories by fans and users.

- Immersion vs. extraction: Immersion implies that users can enter the story with technological or performance strategies that make them feel part of one or several stories. Extraction implies that users take part of the elements of the universe to integrate them in their daily life.

- Construction of new worlds: These are the extensions that give a richer conception of the world where storytelling takes place through experiences in the real and digital world. It is directly related to multiplicity.

- Seriality: It is required that there is a continuity or regularity of both broadcast and storytelling, which allows to follow the central story through the various stories created by the authors of the franchise and by the users.

- Subjectivity: It refers to the exploration of different angles of the central story from the optics of various characters of the franchise. This leads to an exploration by users and fans.

- Execution: The possibility that works made by users and fans become part of the transmedia storytelling itself, when some of these works are accepted by the author.

Something that practically all the authors agree on is the rationalization of the different platforms and containers, which must be fully justified from the expansive planning of the entire transmedia strategy and the logic itself of each one of these resources, avoiding the use of platforms in which the content does not fit or does not make sense to be implemented.

In that order of ideas, one of the most common mistakes that producers and directors make, is to publish contents on a platform that were created for other platforms or containers, believing that this way they are turning their project into a transmedia one, that is to say, for example, a one hour content that was designed for the television screen and then it is uploaded without modifications to YouTube, forcing a story that was planned for the linear television screen, in a digital VoD platform where storytelling and rhythms must be different and times lower. Possibly this type of reposting on other containers and platforms responds more to a Crossmedia model than Transmedia.

Why is it necessary to implement a transmedia strategy?

Unlike decades ago, when the inventory of media and content was equivalent and proportional to the platforms (i.e., there was a radio receiver for radio and a television set for television), nowadays the content inventory is neither proportional nor equivalent to the platforms. Users can watch an audiovisual series on their tablet, cell phone, television set or computer, regardless of whether that content is hosted on an OTT such as Netflix or Youtube, on a traditional television channel or even on social media.

Contemporary consumers have so many options in the technological and convergence universe that it becomes necessary for content to be adapted to that universe, with the additional understanding that users are no longer passive, but participatory subjects who want to play a much more leading role in design and storytelling.

For this reason, transmedia emerges as the best alternative to actively involve the viewer, allowing him/her to consume the story in multiple platforms, settings and containers, while recognizing him/her as a participatory subject in the construction of the story itself and allowing him/her to continue expanding the story in multiple parallel worlds.

You may also be interested in the article: Telcos and Transmedia

By:

Gabriel E. Levy B.